The predictability of hype cycles

"Most predictions are wrong. The small number that turn out to be right are largely luck, but we tend to remember them because they reinforce our naive belief that the future can be predicted."

Every December and January you see lots of prediction of what the new year will bring. Very known predictions are the Gartner Hype Cycle and Horizon report of Educause and the New Media Consortium. If you look at the Horizon Report for 2012 they completely missed the development of MOOCs, while 2012 was declared as Year of the MOOCs by the New York Times.

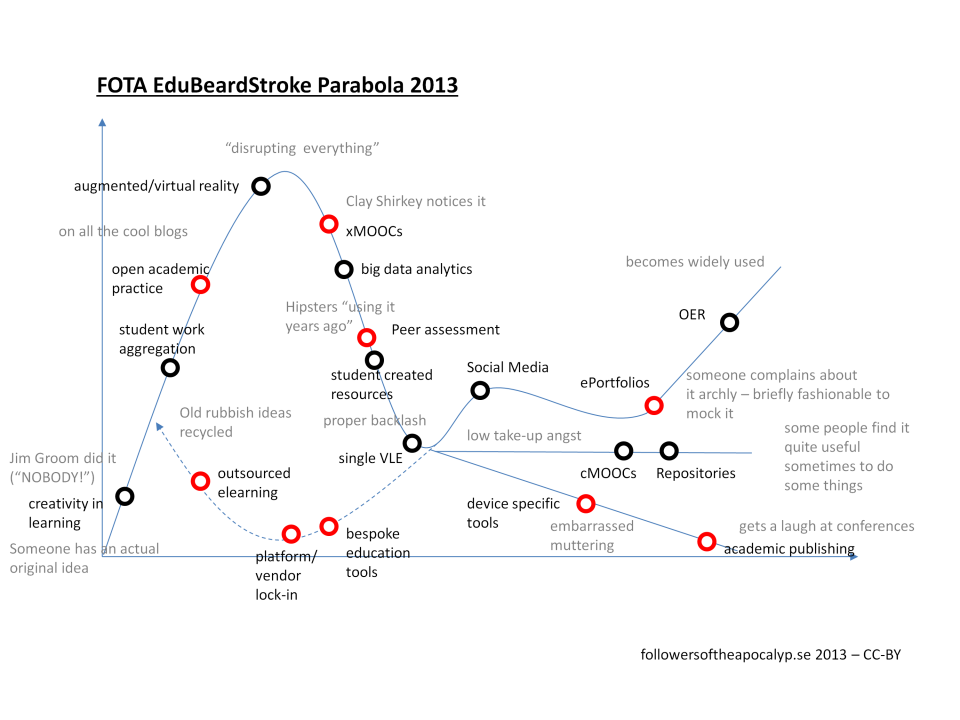

Most of these predictions are based on some sort of research methodology, but also a lot of guessing. This year David Kernohan created a FOTA EdubBeardStroke Parabola 2013. I personally really like the methodology he used to create this:

This diagram was prepared by taking one person who thinks too much about learning technology, leaving them on a train for a stupid amount of time and then marinating in beer and nachos

Darcy Norman raised in his blog a couple of very good points against Gartner's hype cycles:

- it (over)simplifies a concept, reducing it to a single point on a (curvy) line. The only variable is its position on the (curvy) x-axis. And it implies that time (which is the typical x-axis) is all that’s needed. Invent a new shiny thing. Put a dot on the line. And wait. Continue waiting. BOOM! It’s moved through The Cycle, and is now resting happily on The Plateau of Productivity. Awesome! The reason people don’t adopt something early on is because they are dullards who just don’t get how awesome things are. And those that adopt it later are merely sheep who finally wised up and incorporated the inevitable product of time marching on.

- it implies a single shared context. that Shiny Thing #1 is the same thing for everyone, and has the same impact and risks and costs and benefits. That everyone is moving, lock step, together through the inevitable march of time as Shiny Things progress through The Hype Cycle until they reach the point where an organization (it’s always an organization or institution or company – no individuals need apply) is comfortable enough with the risk:benefit ratio and decides to incorporate the inevitable. But this is bullshit. Every organization has a unique context. And individuals matter.

- it provides the Easy Answer. Gartner is in the business of selling reports on extremely complicated or chaotic fields – Big Data, Higher Education, etc… – in order to help organizations and companies to understand change. Buy the report, get the latest Hype Cycle, and you’ll see at a glance where things are at, and what your organization or company needs to do. But easy answers aren’t useful. They placate the CYA MBA crowd who mumble things like “due diligence” and “mitigating risk” etc… while not providing an actual analysis of what these changes mean to their own organization or company. Nope. Gartner said it’s not quite at the peak of inflated expectations, so we have at least 6 months before we have to allocate budget resources to addressing it… – this is the kind of thing Scott points out with his comment on David’s post – it’s probably the biggest danger of this kind of thing. All we need to do is buy access to a report, put a dot on a (curvy) line, and BOOM hey, presto! we’re innovating! we’re adapting to change! To the presentation circuit!

I agree with Darcy and David that we should be careful with the interpretation of hype cycles or parabola. It is an over simplification of the real world. For a university it shouldn't be the main reason to invest in a new development. Just because something is on the hype cycle, it doesn't mean it is the next step for you.

No feedback yet

Form is loading...